The Dene Tha’ historical information presented on this website is excerpted from the Dene Tha’ Traditional Land-Use and Occupancy Study, published in 1997. The purpose of a Traditional Land-Use and Occupancy Study (TLUOS) is to record and illustrate the presence First Nations had, and still continue to have, on the land in their traditional territories; and to record and disseminate traditional knowledge (or traditional environmental knowledge, often known as TEK) to members of the community who do not possess this information, and to those outside of the community who know very little about First Nations people.

For example, instructions regarding the “proper” use of land, and the wisdom of elders regarding hunting, trapping, fishing, and gathering are examples of the type of knowledge that is collected during a TLUOS project. The passing of this type of information in First Nation communities traditionally occurred through the oral tradition of storytelling through generational links; from grandfather to grandson, from mother to daughter. Stories were told by the elders to explain life and how things were properly done.

Unfortunately, the oral tradition of passing on vital information in First Nation communities is slowly being replaced by the written word. This not only reflects a changing lifestyle among First Nations, but an ever-changing society.

Our History - Video

Dene Tha’ Gohndii’ Part 1 of 3

Dene Tha’ Gohndii’ Part 2 of 3

Dene Tha’ Gohndii’ Part 3 of 3

Our History - Photo Galleries

Fixed Sites

Dene Tha’ fixed sites include cabins, camping places and settlement sites. These sites were used by Dene Tha’ as either temporary, overnight camping places, or as more permanent settlement areas.

Dene Tha’ fixed sites include cabins, camping places and settlement sites. These sites were used by Dene Tha’ as either temporary, overnight camping places, or as more permanent settlement areas.

The living conditions of a nomadic lifestyle were often severe, with none of the luxuries that we take for granted today. For example, Sophie Mecredi remembers when her family used a mud fireplace to cook their food, and when there were no lamps used at nighttime.

Even though this lifestyle was not filled with many extras, people described the life on the land, if they had the chance, as one they would gladly return to. Life was hard, but it was also fulfilling.

Dene Tha’ adapted to a more semi-permanent lifestyle around the turn of the century. It was at this time that trading posts were established throughout the area by the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Gradually, the Dene Tha’ settled in small, family-based groups, residing in log cabins that were used seasonally, according to hunting patterns. There are many stories recounted by the Dene Tha’ elders which describe “when we first lived in a log house.” It is only relatively recently that the Dene Tha’ lived any type of sedentary lifestyle in the main contemporary communities.

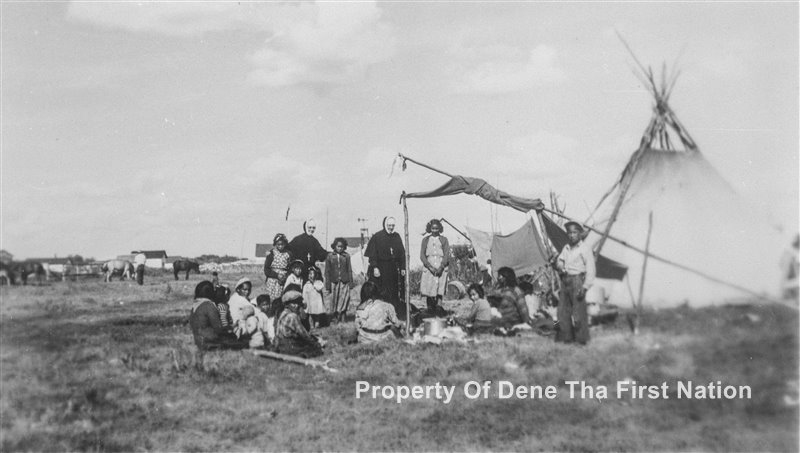

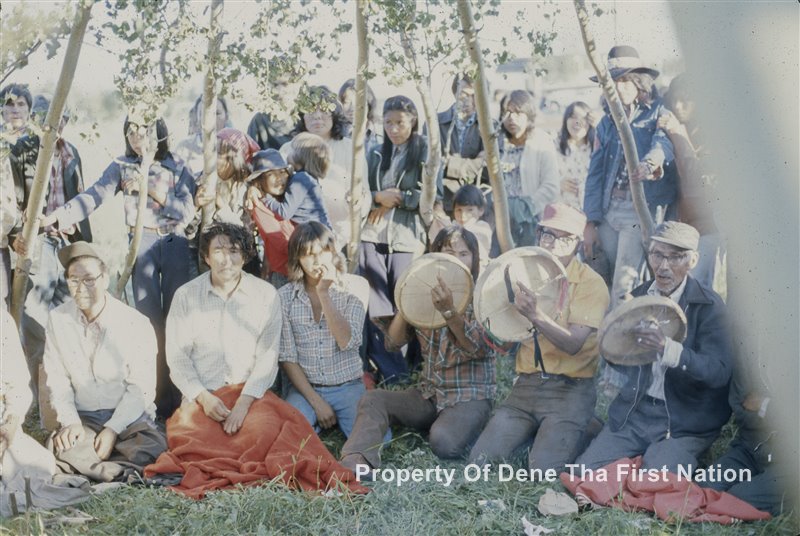

Spirituality

The Dene Tha’ are very spiritual people. Spirituality permeates every facet of life, from how people conduct themselves on the land, to harvesting medicine, to performing Tea Dance ceremonies.

The Tea Dance (or “Dahot s’ethe”) is a deeply religious ceremony for the Dene Tha’. The reason to have a Tea Dance is revealed to the prophets or spiritual leaders of the community through their dreams. A Tea Dance might be held to ask for a successful hunting season, or good weather. It might also be held to commemorate a meeting with another neighbouring community, or as a burial ceremony for someone who has recently died. Tea Dances are still held regularly in Chateh and Meander River, and are very important to the Dene Tha’ culture.

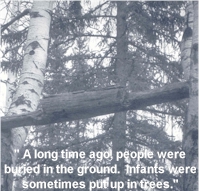

Graves

In the past, people were buried along rivers or trails where people traveled. As a result, many graves have been washed away by the changing current of the river, or by natural erosion of the river banks.

In the past, people were buried along rivers or trails where people traveled. As a result, many graves have been washed away by the changing current of the river, or by natural erosion of the river banks.

The burial markers used by the Dene Tha’ in more recent time are called Spirit Houses, or “Dene K’ih Koanh.” These houses are placed on the grave in a ceremony one year after the actual burial. It was thought that the introduction of the Spirit Houses came from the Crees.

Is has only been relatively recently (the last 150-200 years) that people were buried with any type of grave marker, and more recently still (last 100 years) that Spirit Houses were used to mark burial sites. Bodies were sometimes put into the trees to be “taken” by the birds, or they were put into hollowed-out logs. Often they were wrapped in canvas or tarps and placed in shallow graves in the ground.

People died in great numbers when the “white” sicknesses, such as smallpox, measles and mumps, came to the area. Only the strongest people survived these epidemics.

Hunting

The Dene Tha’ have always been skilled hunters, trappers and fishermen. Hunting skills were passed on from generation to generation, along with vital information regarding animal behaviour and habitat. Good hunters know where animals are at different times of the year, as well as what they eat during the different seasons.

Hunting patterns depended and still depend on many variables, such as weather, previous kills, and availability of game. Hunting trips would last “as long as it took,” said Pierre Ahnassy.

One old method of hunting was to send a scout out to kill a moose ahead of everyone else. Everyone would follow and arrive to make dry meat, and prepare the hide, before moving on to the next kill.

Hunting would last all summer and into the fall.

Moose is probably the most important animal in the lives of the Dene Tha’. It is hunted all year round, although hunting is best during mating season. Every part of the moose is utilized; the hide is tanned and used to make moccasins and clothing, and the meat is either frozen or dried. The viability of the moose as a staple in the Dene Tha’ diet is crucial to the Dene Tha’ elders.

Trapping

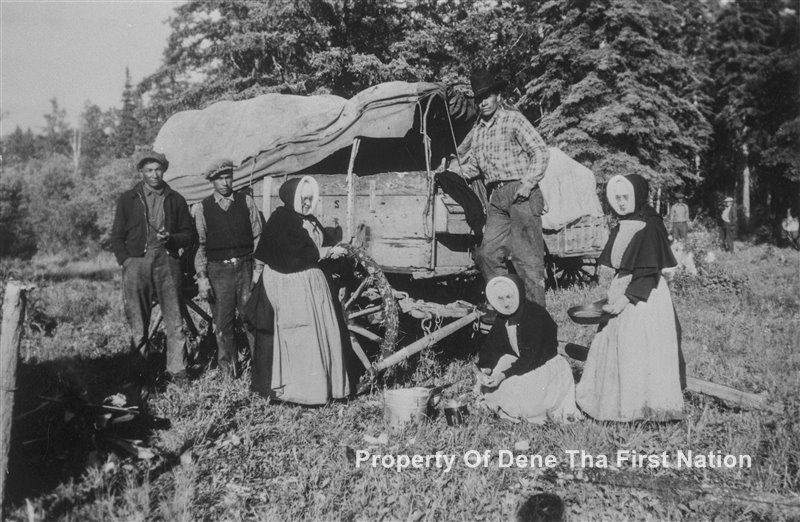

Historical Trading Posts

Outlying trading posts became very important in the lives of the Dene Tha’ after the turn of the century. Several seasonal posts were established by Habay and Long Lake, where goods would only be available in the spring and summer. Longer trips to major trading centres, such as Fort Vermilion and Keg River, would be undertaken for larger trading and shopping trips.

People went to whatever trading post was closest at the time of harvest, or where they knew the fur buyers were going to be. Sometimes, the round trip would take an entire season, with the trapper leaving in the early spring with his furs and not returning until summer with supplies.

Trapping Today

In the past, the Cree from the south acted as “middlemen” in the fur trade, establishing trading posts where they would collect furs from the Dene to the north. In today’s market, the Northwest Company purchases the majority of the fur from the people of Chateh. The fur buyer will come into the community and drive house to house to the known trappers to collect the prepared furs. In January and February, lynx, marten and fox are harvested. In the spring months, beaver and muskrat are harvested.

Despite the economic unpredictability of the fur trade, there are still many active trappers in Chateh, Meander River, and Bushe River. Even though current fur prices remain low, Dene Tha’ trappers still maintain their traplines during the winter months. There is no doubt that if prices were to rise, more Dene Tha’ trappers would return to the traplines. It is a preferred way of life for many people.

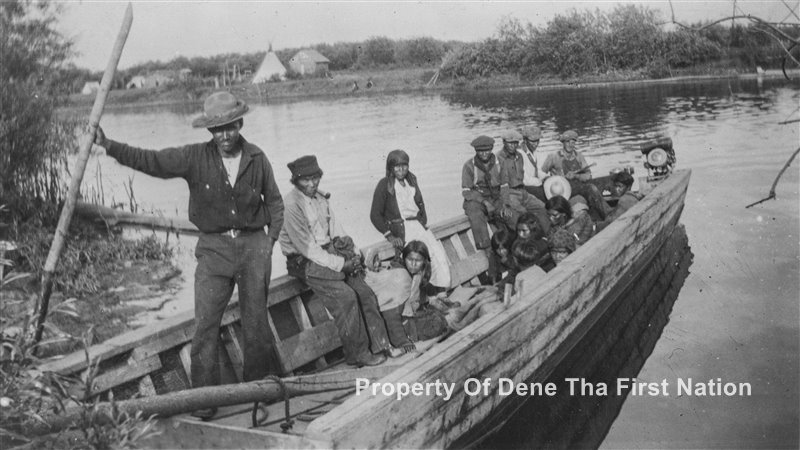

Migration

The Dene Tha’ were constantly on the move, searching for food. However, this nomadic lifestyle was not random; the seasonal migration of people followed very specific patterns. People’s survival depended upon successful hunting patterns.

The Dene Tha’ were constantly on the move, searching for food. However, this nomadic lifestyle was not random; the seasonal migration of people followed very specific patterns. People’s survival depended upon successful hunting patterns.

The Dene Tha’ elders described traveling in a “circular motion,” from Tu Lonh (End of the Water), to Long Lake (Rainbow Lake), to Tamarack Hill, to Tsa Zaghe (Beaver Creek tributary), and back to Tu Lonh on their seasonal searches for game.

Many present day roads and highways were once the Dene Tha’ pack, wagon and horse trails. For example, the Habay Road was once a wagon road used by the Dene Tha’. Today, it is the main route for industry to travel to the Zama oil fields and beyond. The original wagon trail from the Chinchaga River to High Level is also still visible today.

Long ago, people used dog teams or pack dogs to travel from place to place. A team of four to six dogs were used to pull supplies and move equipment. Taking care of the dogs was very important to the survival of the hunter or trapper. Dogs were usually fed before the trapper ate his meal. Today, skidoos are used to travel to places in the winter that are inaccessible by roads. However, dog travel still holds a sentimental place in the hearts of many Dene Tha’ elders.

Names

The overwhelming majority of Dene Tha’ speak Dene as their first language. Naturally then, each person usually has a Dene name and an English name. “Before the missionaries came, the Dene newborns were named by the elders.

The overwhelming majority of Dene Tha’ speak Dene as their first language. Naturally then, each person usually has a Dene name and an English name. “Before the missionaries came, the Dene newborns were named by the elders.

Surnames were unknown after the child became of age, their names were changed to the names of animals that they first killed. A number of children were named for their behavior or whatever their parents wanted to call them. Nowadays, these old names sound funny to recall,” said Louise Hooka Nooza.

Places within the Dene Tha’ traditional territory also have Dene names. One difficulty in identifying these Dene place names is that different family groups have their own names for places. As a result, there may be more than one name for a particular place.